Traduciamo e condividiamo l’inchiesta del giornale Correctiv, ossia il resoconto di un loro “imbucato” all’incontro segreto tenutosi il 25 Novembre a Potsdam tra estremisti di destra, frontman di AFD e ricchi simpatizzanti.

Un resoconto che a definire allarmante sarebbe sputare sulla definizione stessa del termine.

Ne consigliamo la lettura, se non altro nell’ottica del comprendere maggiormente le motivazione alla base delle proteste nelle piazze tedesche dell’ultima settimana.

Buona lettura

Un po’ alla volta, la luminosa sala da pranzo di un hotel di campagna vicino a Potsdam si riempie di persone. Sono circa due dozzine, un mix di membri dell’AfD, seguaci del movimento identitario e membri di confraternite studentesche nazionaliste (Burschenschaft). Tra i partecipanti ci sono anche persone della classe media, medici, avvocati, politici e imprenditori. Anche due membri del partito cristiano-democratico di centro della Germania (CDU) hanno partecipato, entrambi facenti parte dell’associazione di base conservatrice “Unione dei Valori” del loro partito (WerteUnion).

Solo di recente è stato pubblicato su Die Zeit un profilo dettagliato di una delle proprietarie dell’hotel, che descrive i suoi stretti legami con gli ambienti di destra.

Ci sono due uomini dietro gli inviti a questo evento. Il primo ha circa 60 anni ed è stato coinvolto nella scena dell’estrema destra tedesca per la maggior parte della sua vita. Si chiama Gernot Mörig, un ex dentista di Düsseldorf. L’altro è Hans Christian Limmer, un noto investitore nel settore della ristorazione. Limmer è stato artefice del successo della catena tedesca di panetterie discount BackWerk e oggi è azionista della catena tedesca di hamburger alla moda Hans im Glück. A differenza di Mörig, Limmer non è presente all’evento in prima persona, ma svolge comunque un ruolo di ricco facilitatore.

Prologo: Dietro le quinte

Il 25 novembre. È un cupo sabato mattina, poco prima delle nove. La neve si posa sulle auto parcheggiate nel cortile. Gli eventi che si svolgeranno oggi all’hotel Landhaus Adlon sembreranno un dramma distopico. Solo che sono reali. E mostreranno cosa può accadere quando i frontman delle idee estremiste di destra, i rappresentanti dell’AfD e i ricchi simpatizzanti si riuniscono. Il loro obiettivo comune è la deportazione forzata di persone dalla Germania sulla base di una serie di criteri razzisti, indipendentemente dal fatto che abbiano o meno la cittadinanza tedesca.

L’incontro doveva rimanere segreto a tutti i costi. Le comunicazioni tra gli organizzatori e gli invitati avvenivano rigorosamente per lettera. Tuttavia, copie di queste lettere sono trapelate a CORRECTIV e noi le abbiamo fotografate. Il nostro reporter in incognito si è registrato nell’hotel sotto falso nome e si è recato sul posto con una telecamera. Ha potuto filmare davanti, dietro e persino all’interno dell’hotel. Il nostro resoconto di prima mano ci dice esattamente cosa è successo durante le riunioni e chi c’era. Anche Greenpeace si è documentata sull’incontro e ci ha fornito importanti foto e copie di documenti. Il nostro reporter ha parlato con diversi membri dell’AfD presenti nell’hotel e altre fonti ci hanno confermato le loro dichiarazioni.

E così abbiamo potuto ricostruire gli eventi dell’hotel.

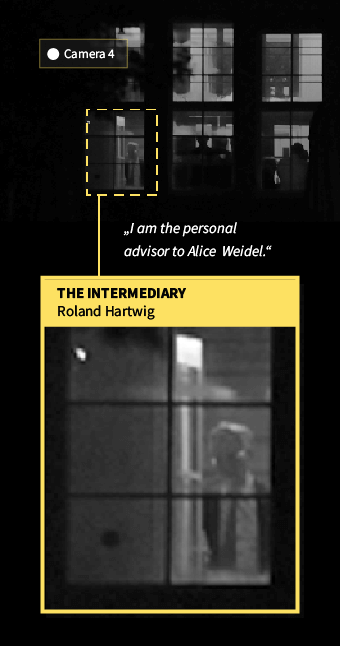

È stato molto più di un incontro di ideologi di destra. Alcuni sono incredibilmente ricchi. Altri hanno molta influenza all’interno dell’AfD. Uno di loro risulta avere un ruolo chiave in questa storia. All’hotel si è vantato di parlare a nome del direttivo del partito AfD. È l’assistente personale di Alice Weidel.

A soli dieci mesi dalle elezioni regionali negli Stati tedeschi di Turingia, Sassonia e Brandeburgo, questo incontro ha dimostrato che gli atteggiamenti razzisti si estendono ai vertici del partito AfD. E non ci si ferma agli atteggiamenti; alcuni politici vogliono mettere in pratica le loro idee razziste, nonostante l’AfD neghi fermamente di essere un partito estremista di destra.

Queste rivelazioni potrebbero essere molto incriminanti per l’AfD, visto il contesto dei recenti dibattiti sull’opportunità di mettere al bando il partito come minaccia alla democrazia del Paese. Allo stesso tempo, offrono uno spaccato sinistro di ciò che potrebbe accadere se l’AfD dovesse mai salire al potere.

I piani elaborati nel fine settimana a Potsdam non sono altro che un feroce attacco alla stessa Costituzione tedesca.

I partecipanti

AFD

Roland Hartwig, assistente personale della leader del partito Alice Weidel

Gerrit Huy, deputato Ulrich Siegmund, capogruppo parlamentare per la Sassonia-Anhalt

Tim Krause, presidente del partito distrettuale di Potsdam

IL CLAN MÖRIG

Gernot Mörig, dentista in pensione di Düsseldorf

Arne Friedrich Mörig, figlio di Gernot Mörig

Astrid Mörig, moglie di Gernot Mörig

NEO-NAZIS

Martin Sellner, attivista austriaco di estrema destra

Mario Müller, condannato per reati violenti Un giovane “identitario” senza nome

OSPITI

Wilhelm Wilderink

Martina Mathilda Huss

ALTRE ORGANIZZAZIONI

Simone Baum, presidente dell'”Associazione dell’Unione dei Valori” (Werteunion) della Renania Settentrionale-Vestfalia

Michaela Schneider, vicepresidente dell'”Associazione dell’Unione dei Valori” (Werteunion) della Renania Settentrionale-Vestfalia

Silke Schröder, presidente dell'”Associazione della Lingua Tedesca” (Verein Deutsche Sprache) Ulrich Vosgerau, ex membro del consiglio di amministrazione della Fondazione Erasmus.

I RESTANTI

Alexander von Bismarck Henning Pless, esoterista di estrema destra, praticante di medicina alternativa

Un uomo d’affari del settore informatico e nazista sfegatato

Un neurochirurgo austriaco

Due impiegati dell’hotel

Atto 1, scena 1: Un hotel sul lago

Il grande albergo del 1920 si trova alla periferia di Potsdam. Ha un tetto di tegole e una vista sul vicino lago Lehnitz. I primi ospiti arrivano il venerdì sera. Una 4×4 bianca proveniente dalla Bassa Sassonia si ferma e dal finestrino esce una canzone della band Frei.Wild: Wir, wir, wir, wir schaffen Deutschland (Noi, noi, noi, stiamo creando la Germania).

La mattina dopo arrivano altri ospiti. All’interno dell’hotel, si dirigono sul parquet verso un tavolo bianco apparecchiato con una trentina di piatti, ciascuno con un tovagliolo ripiegato. Molti di loro hanno ricevuto inviti personali contenenti tutte le informazioni sull’evento. Gli inviti del “Forum di Düsseldorf”, come si fa chiamare il gruppo, parlano di una “rete esclusiva” e di una “donazione minima” di 5.000 euro. La raccolta di fondi è un “compito fondamentale del nostro gruppo”, affermano. E sembra che stiano perseguendo attivamente questo obiettivo, sollecitando denaro da ricchi uomini d’affari che vogliono sostenere alleanze di estrema destra in segreto. “Abbiamo bisogno di patrioti pronti ad agire e di individui che sostengano finanziariamente le loro attività”, si legge nell’invito. Una volta giunti all’incontro, gli organizzatori dell’evento annunceranno un “conto bancario neutrale”, oppure la donazione potrà essere versata anche in contanti, hanno assicurato i lettori.

Ma a cosa servono le donazioni?

Lo scopo delle donazioni è accennato negli inviti, che sono firmati dagli organizzatori Mörig, il dentista, e Limmer, l’ex azionista di Backwerk. In un’altra copia dell’invito visionata da CORRECTIV, Mörig parla di “un concetto generale nel senso di un masterplan”. Il masterplan sarà presentato, annuncia con orgoglio, da “nientemeno che” Martin Sellner, il leader di lunga data del movimento di estrema destra Identitarian. Chiunque abbia partecipato a questo fine settimana in hotel sapeva di cosa si sarebbe trattato.

Atto 1, scena 2: Un piano per liberare il Paese dagli immigrati

Sellner, autore e figura di spicco della Nuova Destra europea, è il primo oratore della giornata. Nell’introduzione di Mörig, il pubblico viene informato che Sellner ha “il piano generale”, che ruota attorno a un’idea chiave: la “ri-migrazione”.

È l’idea di Sellner di ri-migrazione che dovrebbe essere il punto focale di questo incontro, dice Mörig. Tutto il resto – le restrizioni sui vaccini e le vaccinazioni, le questioni dell’Ucraina e di Israele – sono tutti argomenti di contestazione per la destra. La loro posizione sulla reimmigrazione, tuttavia, è ciò che li unisce. Mörig ritiene che sarà decisivo per stabilire “se noi occidentali sopravviveremo o meno”.

La maggior parte delle presentazioni e delle discussioni di oggi si concentreranno su questo concetto.

Prende ora la parola Sellner. Nel suo discorso spiega nei dettagli cosa significherebbe la ri-migrazione in Germania. Ci sono tre gruppi di migranti, spiega, che dovrebbero essere estradati dal Paese – o, come dice lui, “stranieri” che dovrebbero essere sottoposti a “insediamento inverso”. Si tratta di richiedenti asilo, non tedeschi con diritto di residenza e cittadini tedeschi “non assimilati”. Sono questi ultimi che, a suo avviso, rappresenterebbero la “sfida” più grande. In altre parole, il piano di Sellner dividerebbe i residenti tedeschi in coloro che sarebbero in grado di vivere pacificamente in Germania e coloro per i quali questo diritto umano fondamentale non sarebbe più applicabile.

Gli scenari abbozzati in questa stanza d’albergo a Potsdam si riducono tutti essenzialmente a una cosa: le persone in Germania dovrebbero essere estradate con la forza se hanno il colore della pelle sbagliato, i genitori sbagliati o non sono sufficientemente “assimilate” nella cultura tedesca secondo gli standard di persone come Sellner. Anche se hanno la cittadinanza tedesca.

È uno scenario che contravverrebbe ai diritti di cittadinanza e al principio di uguaglianza tra i cittadini che sono un fondamento della Costituzione tedesca.

Il concetto di “ri-migrazione” dell’estrema destra.

Le idee di Sellner non sono nuove. Nel suo libro “Cambio di regime da destra”, pubblicato nel 2023 dalla casa editrice dell’attivista dell’estrema destra tedesca Götz Kubitschek, egli descrive come:

“L’obiettivo principale della destra” è la conservazione dell'”identità e integrità etnoculturale”, che richiede “una svolta radicale” per fermare l’attuale “scambio di popolazione”. A tal fine, è necessaria “una politica di ri-migrazione”. Sellner chiede una “revisione” delle cittadinanze esistenti e fa riferimento ai “concetti rilevanti dei partiti e dei movimenti di destra” in questo ambito. Il libro non è difficile da capire. Si tratta di preparare le deportazioni di massa.

Gli stretti legami tra Sellner e alcuni politici dell’AfD, evidenti in questo incontro, non sono una novità. La casa editrice Kubitschek offre il libro di Sellner in un cofanetto insieme al manifesto di Maximillian Krah – Krah è il candidato dell’AfD alle elezioni europee. Il suo libro, “Politica di destra – un manifesto”, chiede l’abbandono dei diritti umani universali e invoca la “ri-migrazione” dei “cittadini”. Krah sostiene che “anche se una politica restrittiva sull’immigrazione potesse essere politicamente applicata tra 10 anni, resta da chiedersi cosa accadrebbe a tutti gli immigrati già presenti nel Paese”. Secondo le sue stime, a quel punto gli immigrati sarebbero circa “25 milioni […] di cui 15 milioni sarebbero cittadini tedeschi”. Teme che “anche tra dieci anni non ci sarà una maggioranza politica disposta a espellere queste persone dal Paese contro la loro volontà, né tantomeno un modo per farlo legalmente in base al diritto costituzionale e internazionale”.

Atto 1, scena 3: Nessuna obiezione da parte dell’AfD, nonostante la recente discussione pubblica per la messa al bando del partito per estremismo.

A questo discorso seguono molte domande di sostegno. Non ci sono obiezioni al “masterplan” in linea di principio, ma solo preoccupazioni sulla sua fattibilità.

Silke Schröder, promotrice immobiliare e membro del consiglio di amministrazione dell’associazione di destra Verein Deutsche Sprache (Associazione della lingua tedesca), si chiede come funzionerebbe in pratica la reimmigrazione. Sicuramente se una persona ha il passaporto “appropriato” sarebbe “impossibile”, non è vero?

Per Sellner, questo è solo un dettaglio. Secondo Sellner, si eserciterà un “alto livello di pressione” sulle persone affinché si adattino, attraverso “leggi personalizzate”. La riemigrazione non avverrà da un giorno all’altro; è “un progetto che richiederà decenni”.

I membri dell’AfD presenti in sala non sono certo contrari all’idea. Al contrario, il deputato Gerrit Huy ha sottolineato che lei persegue questo obiettivo da anni.

Huy ha affermato di aver presentato al partito un “concetto di ri-migrazione” quando si è iscritto per la prima volta sette anni fa. I piani per la ri-migrazione erano il motivo per cui il partito non si opponeva più al progetto del governo di abolire il divieto di doppia cittadinanza, ha detto, “perché così si può togliere quella tedesca, e a loro ne rimane una”. Le dichiarazioni di Huy suggeriscono che gli immigrati con passaporto tedesco possono essere attirati in una trappola.

Anche il capogruppo dell’AfD in Sassonia-Anhalt, Ulrich Siegmund, è presente in sala. È lui che, più tardi nel corso della giornata, farà appello alle donazioni. Ha una notevole influenza all’interno dell’AfD; il partito è attualmente al primo posto nei sondaggi in Sassonia-Anhalt. Il suo discorso di vendita, molto in linea con il “masterplan” di Sellner, illustra le sue idee per cambiare l’immagine delle strade tedesche. I ristoranti stranieri verrebbero messi sotto pressione. La vita in Sassonia-Anhalt dovrebbe essere resa “il meno attraente possibile per questa clientela”. E questo potrebbe essere realizzato molto, molto facilmente, sostiene. I suoi commenti potrebbero avere conseguenze sulle prossime elezioni della regione.

Sostenuto dal recente aumento di popolarità, l’AfD si sente ottimista. Il generale spostamento a destra del Paese ha dato una spinta al partito. Attualmente è in testa nei sondaggi con oltre il 30% in diversi Stati, tra cui la Sassonia e la Turingia, davanti a CDU, SPD e Verdi. Tuttavia, il partito è anche sotto pressione. L’Ufficio federale per la protezione della Costituzione (Bundesverfassungsschutz), l’agenzia di intelligence interna della Germania, ha classificato le sezioni dell’AfD in Turingia, Sassonia-Anhalt e Sassonia come gruppi estremisti di destra. Più recentemente, ha classificato l’ala giovanile dell’AfD della Renania Settentrionale-Vestfalia, Junge Alternative, come sospetto gruppo estremista. Le ragioni addotte sono state la sua vicinanza al movimento identitario, le sue opinioni “etno-nazionaliste” e il suo “disprezzo per le persone con un background di immigrazione”.

Il dibattito sull’opportunità di vietare l’AfD sta prendendo sempre più piede. Una petizione che chiede la messa al bando del partito ha raccolto oltre 400.000 firme e il deputato della CDU Marco Wanderwitz sta attualmente raccogliendo consensi nel Bundestag (il parlamento tedesco) per chiedere una mozione di messa al bando del partito.

L’AfD stesso, tuttavia, continua a ribadire di essere una forza democratica. “L’AfD è un partito politico che si basa sullo stato di diritto, e pertanto dichiara la sua inequivocabile fedeltà alla nazione tedesca, che comprende tutti coloro che hanno la cittadinanza tedesca”, si legge sul suo sito web. Gli immigrati con cittadinanza tedesca sono “tedeschi quanto i discendenti di una famiglia che vive in Germania da secoli”. “Per noi non esistono cittadini di prima e seconda classe”, proseguono.

Le dichiarazioni dei politici dell’AfD all’incontro di Potsdam suggeriscono convinzioni molto diverse. Qui, al riparo dagli occhi del pubblico, non hanno problemi a proclamare i loro ideali razzisti. In effetti, non ci sono differenze significative tra le loro opinioni e quelle degli ideologi di estrema destra.

Atto 1, scena 4: Un’utopia nazista

Fuori la neve si sta trasformando in fanghiglia. Ma all’interno dell’hotel il morale è alto. Gernot Mörig racconta agli ospiti che di solito è un tipo piuttosto pessimista, ma oggi si sente fiducioso. E questo grazie anche al “masterplan” di Sellner.

Il masterplan include persino una destinazione in cui “trasferire le persone”, un cosiddetto “Stato modello” in Nord Africa, che a quanto pare offrirebbe spazio a due milioni di persone. Lì ci sarebbero anche offerte educative e sportive. E chiunque faccia pressioni a favore dei rifugiati potrebbe raggiungerli lì, ha aggiunto Sellner.

L’idea di Sellner ricorda molto da vicino il piano nazista del 1940 di deportare quattro milioni di ebrei sull’isola di Madagascar. Non è chiaro se Sellner avesse in mente questo parallelo storico quando ha ideato il suo piano. Potrebbe anche essere una mera coincidenza che gli organizzatori dell’evento abbiano scelto un luogo a meno di 8 chilometri dalla villa in cui si svolse la Conferenza di Wannsee, la riunione in cui i nazisti coordinarono lo sterminio sistematico degli ebrei.

Tornato in albergo, Sellner passa a un altro argomento che infiamma l’estrema destra, il problema del cosiddetto “voto etnico”. Ha persino registrato il termine come nome di dominio. Secondo Sellner, il problema “non è solo che gli stranieri vivono qui. Votano anche qui”. Il “voto etnico” significa che gli immigrati sono propensi a votare per i partiti “favorevoli all’immigrazione”.

Le argomentazioni di Sellner non sono solo tentativi di delegittimare le elezioni, ma trattano anche i cittadini tedeschi come stranieri nel loro stesso Paese. Secondo l’ufficio tedesco per le statistiche nazionali (Statistisches Bundesamt), 20,2 milioni di tedeschi hanno una “storia di immigrazione”, cioè sono immigrati in Germania dal 1950 o i loro genitori.

Gli eventi dell’hotel di Potsdam chiariscono come si intrecciano le strategie di diversi attori e organizzazioni di estrema destra. Sellner fornisce le idee, i politici dell’AfD le fanno proprie e le portano nel partito. Altri, sullo sfondo, si occupano di fare rete e di coinvolgere ricchi simpatizzanti e sostenitori della borghesia conservatrice. I dibattiti ruotano sempre intorno a una domanda: Come si può realizzare una comunità etnica omogenea in Germania?

Atto 2, Scena 1: Influencer che aiutano a realizzare il masterplan

La discussione si sposta ora sui dettagli pratici, sui passi da compiere. Mörig vuole selezionare un comitato di esperti per mettere a punto i dettagli di questo piano di deportazioni di massa. Questi esperti si assicureranno che il piano sia eseguito “in modo etico, legale ed efficiente”, in modo che il trasferimento forzato di persone a sfondo razziale abbia le sembianze di una politica migratoria legale. Mörig ha già in mente un candidato per il comitato: Hans-Georg Maaßen, ex capo dell’Ufficio federale per la protezione della Costituzione (Bundesverfassungsschutz), l’agenzia di intelligence nazionale tedesca.

Il nome di Maaßen è emerso più volte nel corso del fine settimana. Secondo diversi rapporti, a gennaio dovrebbe annunciare il lancio di una propria associazione politica. I partecipanti all’incontro di Potsdam ne sono già a conoscenza. Pur menzionando il nuovo gruppo in diverse occasioni, non sembrano prenderlo troppo sul serio. Sono più preoccupati dei loro piani e di come si realizzeranno quando, secondo le parole di Mörig, “una forza patriottica sarà al potere in questo Paese”.

L’attenzione del gruppo si sposta ora su come l’idea della ri-migrazione possa essere trasformata in una strategia politica. Secondo Sellner, è necessario costruire un “potere metapolitico e pre-politico” per “cambiare l’opinione pubblica”. Un fronte politico attivo deve essere pronto a sostenere il prossimo governo di destra in Germania dopo le elezioni.

E parte di questo sostegno, come viene chiarito durante le presentazioni e i discorsi, deve essere di tipo finanziario. Si parla di influencer, propaganda, campagne e progetti universitari. Gli strumenti per instaurare un clima di destra anti-establishment. E infine gli strumenti per indebolire la democrazia tedesca mettendo in discussione le elezioni, screditando la Corte costituzionale, sopprimendo le opinioni contrarie e censurando il servizio pubblico radiotelevisivo.

Atto 2, scena 2: Come se l’equilibrio del potere si fosse già ribaltato

Un oratore segue l’altro, gli interventi durano circa un’ora ciascuno. A metà del pranzo, la cameriera sembra irritata dal gran numero di ospiti che deve accogliere.

Nel pomeriggio è il turno di Ulrich Vosgerau. È un avvocato ed è stato membro del consiglio di amministrazione della Fondazione Desiderius Erasmus, affiliata all’AfD, e attualmente rappresenta l’AfD presso la Corte costituzionale tedesca in una controversia sul finanziamento della fondazione.

Parla del voto per corrispondenza, dei processi legali, della segretezza del voto e delle sue preoccupazioni per gli elettori di origine turca che, a suo dire, non sono in grado di formarsi un’opinione indipendente. Vosgerau suggerisce di redigere una lettera che metta in dubbio la legittimità delle prossime elezioni. Più persone partecipano, più alte sono le probabilità di successo della lettera. Il suo discorso viene accolto da un applauso.

Vosgerau e gli altri parlano come se la bilancia del potere si fosse già ribaltata a loro favore. Credono chiaramente di essere sul punto di fare un passo avanti. Mario Müller, membro del movimento identitario e delinquente violento con diverse condanne a suo carico, è attualmente assistente di ricerca del deputato dell’AfD Jan Wenzel Schmidt. Anche nel suo discorso, Müller parla come se la vittoria fosse già in vista.

Atto 3, scena 1: Il clan Mörig

Dalle finestre a grata dell’hotel si intravedono i partecipanti a questa riunione segreta. La grande sala da pranzo emana un’atmosfera di antico splendore, un clavicembalo in un angolo, un orologio a pendolo in un altro. Molti degli invitati sono in giacca e cravatta.

Le cose sembrano andare bene e i piani sono stati elaborati, o almeno delineati. Ma tutto si regge sui finanziamenti, cosa che Gernot Mörig sa bene. Negli anni ’70, Mörig era a capo della “Lega della Gioventù Patriottica” (Bund Heimattreuer Jugend), un’organizzazione giovanile di estrema destra che promuoveva l’ideologia nazista “sangue e suolo”. Un gruppo scissionista, i “Giovani patrioti tedeschi” (Heimattreue deutsche Jugend), è stato bandito nel 2009 a causa del suo programma neonazista. Il gruppo era talmente di destra che Andreas Kalbitz, ex leader dell’AfD nel Brandeburgo, fu espulso dal partito quando si scoprì che era stato ospite di uno dei loro campi.

È stato Mörig a scegliere gli ospiti e a stabilire l’ordine del giorno di questo incontro segreto. Fu lui a scrivere del “piano regolatore” nei suoi inviti e a chiedere donazioni agli invitati. Durante l’evento chiede agli ospiti di consegnare “discretamente” le loro donazioni in denaro a sua moglie. In seguito, spiega che il denaro raccolto sarà utilizzato per sostenere organizzazioni più piccole, come quella di Martin Sellner.

Ciò significa che tutti gli ospiti che hanno donato denaro lo hanno fatto sapendo di finanziare il movimento identitario e lo stesso Sellner. Ma Mörig sta per chiedere ancora di più.

Presenta ai presenti un elenco di sostenitori che presumibilmente vogliono donare denaro o lo hanno già fatto, comprese persone non presenti all’evento. Christian Goldschagg, fondatore della catena di palestre Fit-Plus ed ex azionista della casa editrice Süddeutscher; Klaus Nordmann, uomo d’affari della classe media della Renania Settentrionale-Vestfalia e grande donatore dell’AfD; Alexander von Bismarck, ad esempio, che ha attirato l’attenzione con la sua comprensione della Russia e una bizzarra campagna elettorale l’anno scorso, è seduto nella stanza. Mörig è molto disponibile a fare nomi e cognomi. Si vanta di coloro che hanno già donato “somme a quattro zeri” e di coloro che hanno promesso di farlo. In precedenza, le donazioni venivano convogliate attraverso il conto privato del cognato banchiere, ma ora ha in mente una soluzione più professionale. Chi si sente più a suo agio può lasciare una donazione in contanti alla moglie, ma “entro la prossima riunione probabilmente avremo anche un’associazione non registrata” attraverso la quale si potranno effettuare bonifici bancari, dice agli ospiti.

Atto 3, scena 2: Un politico dell’AfD chiede milioni in donazioni dirette

Anche Ulrich Siegmund, capogruppo parlamentare dell’AfD in Sassonia-Anhalt, ha bisogno di denaro. Sta già pensando alle prossime elezioni e agli annunci elettorali che vuole inviare, preferibilmente direttamente nelle cassette delle lettere dei cittadini. Vuole che a ogni elettore venga scritto almeno una volta. Sarà necessaria anche la tradizionale pubblicità radiofonica e televisiva. E ha bisogno di denaro “in aggiunta a quello fornito dal partito”, per la precisione 1,37 milioni di euro in più. Potrebbe trattarsi di un tentativo di aggirare i fondi ufficiali del partito, convogliando il denaro direttamente a lui. L’AfD ha già diversi scandali legati alle donazioni.

Le donazioni ufficiali del partito sono “di gran lunga il modo più sicuro” di fare donazioni, dice Siegmund. “Tuttavia”, ci sono altri “modi assolutamente legali per fare donazioni”. Suggerisce di rivolgersi ad “agenzie” e “terze parti”. Gli ospiti sono invitati a venire a discutere le opzioni con lui separatamente per trovare “l’opzione migliore per ogni individuo”.

Atto 3, scena 3: Il braccio destro di Alice Weidel

Il fatto che parti dell’AfD abbiano stretti legami con i neonazisti e la Nuova Destra non è una novità. Finora, tuttavia, il partito ha attribuito la responsabilità del problema alle sedi regionali e locali.

Ma un politico di spicco dell’AfD era presente all’incontro con gli estremisti di destra a Potsdam. Si tratta di Roland Hartwig, ex deputato dell’AfD e ora assistente personale della leader del partito, Alice Weidel. Secondo diversi addetti ai lavori del governo dell’AfD, Hartwig è il “segretario generale non ufficiale del partito”, una persona che esercita un’influenza significativa sui più alti livelli decisionali del partito.

Hartwig dichiara di essere un grande fan del nuovo libro di Sellner, che gli sta “piacendo molto”. Parla anche del “piano regolatore” e prosegue dicendo che l’AfD sta attualmente elaborando un prototipo di causa contro le emittenti pubbliche tedesche. Questo si aggiunge a una campagna che, a suo dire, sta pianificando per dimostrare quanto siano sovrafinanziate le emittenti.

Anche il figlio di Mörig ha un piano da presentare alla conferenza. Si inserisce perfettamente nelle idee di Sellner. Arne Friedrich Mörig vuole creare un’agenzia per gli influencer di destra. Hartwig accenna alla possibilità che l’AfD possa cofinanziare l’agenzia. Ciò consentirebbe loro di influenzare le elezioni, sottolinea Hartwig, soprattutto attraverso i giovani. “La generazione che deve cambiare il gioco politico è già presente”, afferma, e l’AfD intende rivolgersi ai giovani su piattaforme come TikTok e YouTube con contenuti che normalizzino le idee del partito.

Secondo Hartwig, il prossimo passo di questo progetto sarà ora quello di presentare il piano al consiglio nazionale del partito AfD e di convincere il partito a trarre vantaggio da un investimento nell’agenzia di influencer di Mörig.

Verso la fine, Hartwig fa una dichiarazione cruciale: “Il nuovo Consiglio del partito, in carica da un anno e mezzo, è aperto a questo tema. Siamo quindi disposti a prendere in mano il denaro e a portare avanti questioni che non vanno direttamente a vantaggio del solo partito”.

Hartwig dà la netta impressione di agire come intermediario per il direttivo del partito AfD, con il compito di comunicare loro il contenuto di questo incontro. Al momento di andare in stampa non ha risposto alle nostre domande sull’incontro.

Epilogo

La sera seguente tutto è tranquillo. L’hotel sembra quasi completamente deserto. Dalla finestra di una delle suite si vede solo il tremolio di uno schermo televisivo.

Cosa abbiamo appreso da questo incontro?

Che c’è un dentista in pensione che ha una rete cospirativa di compagni estremisti di estrema destra. Che i rappresentanti dell’AfD erano disposti a incontrare attivisti della destra radicale e neonazisti. Che hanno un “piano generale” per deportare i cittadini tedeschi a causa della loro “etnia” – un piano che minerebbe gli articoli 3, 6 e 21 della Costituzione tedesca. E che ci sono diversi ricchi potenziali donatori per questo progetto. Abbiamo appreso che c’è un esperto di diritto costituzionale tedesco che ha abbozzato metodi legali per mettere sistematicamente in dubbio le elezioni democratiche. Che c’è un politico dell’AfD che vuole organizzare donazioni elettorali che bypassino il partito. E che c’è un albergatore di Potsdam che ha guadagnato un po’ di soldi per coprire le spese.

ENGLISH (ARTICLE ORIGINAL VERSION)

People from the middle classes – doctors, lawyers, politicians and entrepreneurs – are also among the participants. Even two members of Germany’s centre-right Christian Democratic Party (CDU) have come along, both part of their party’s grassroots conservative ‘Values Union’ association (WerteUnion).

A detailed profile of one of the hotel’s owners has only recently been published in Die Zeit, detailing her close ties to right-wing circles.

There are two men behind the invitations to this event. The first is in his late 60s and has been involved in the far-right scene in Germany for most of his life. His name is Gernot Mörig, a former dentist from Düsseldorf. The other is Hans Christian Limmer, a well-known investor in the catering sector. Limmer was behind the success of the German discounter bakery chain BackWerk, and today is a shareholder in the trendy German burger chain Hans im Glück. Unlike Mörig, Limmer is not at the event himself, but nevertheless plays a role as wealthy facilitator.

Prologue: Behind the scenes

The 25th of November. It is a gloomy Saturday morning, shortly before nine o’clock. Snow is settling on the cars parked in the courtyard. The events that will occur today at the hotel Landhaus Adlon will seem like a dystopian drama. Only they’re real. And they will show what can happen when the frontmen of right-wing extremist ideas, representatives of the AfD and wealthy sympathisers come together. Their shared goal is the forced deportations of people from Germany based on a set of racist criteria, regardless of whether or not they have German citizenship.

The meeting was meant to remain secret at all costs. Communications between the organisers and guests took place strictly via letters. However, copies of these letters were leaked to CORRECTIV, and we took pictures. Our undercoverreporter checked into the hotel under a false name and was on site with a camera. He was able to film in front, behind and even inside the hotel. Exactly what went on in the meetings, and who was there, comes from our first-hand report. Greenpeace had also been researching the meeting and provided us with important photos and copies of documents. Our reporter spoke to several AfD members at the hotel, and further sources have confirmed their statements to us.

And so we could reconstruct the events at the hotel.

It was much more than a coming together of right-wing ideologues. Some are incredibly rich. Others have a lot of influence within the AfD. One of them turns out to play a key role in this story. At the hotel, he boasted that he spoke for the AfD party board. He’s Alice Weidel’s personal aide.

With only ten months to go until the regional elections in the German states of Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg, this meeting has shown that racist attitudes extend into the highest echelons of the AfD party. And it doesn’t stop with attitudes; certain politicians want to put their racist ideas into action, despite the fact the AfD firmly denies that it is a right-wing extremist party.

These revelations could be highly incriminating for the AfD, given the context of recent debates about whether the party should be banned as a threat to the country’s democracy. At the same time, it gives a sinister glimpse into what could happen should the AfD ever come to power.

The plans that were drafted on this weekend in Potsdam are nothing less than a fierce attack on the German constitution itself.

The People

AFD

Roland Hartwig, personal aide to party leader Alice Weidel

Gerrit Huy, MP

Ulrich Siegmund, parliamentary group leader for Saxony-Anhalt

Tim Krause, chair of the district party in PotsdamTHE MÖRIG CLAN

Gernot Mörig, a retired dentist from Düsseldorf

Arne Friedrich Mörig, Gernot Mörig’s son

Astrid Mörig, Gernot Mörig’s wifeNEO-NAZIS

Martin Sellner, Austrian far-right activist

Mario Müller, a convicted violent offender

An unnamed young “Identitarian”HOSTS

Wilhelm Wilderink

Martina Mathilda HussFURTHER ORGANISATIONS

Simone Baum, chair of the ‘Values Union Association’ (Werteunion) in North Rhine-Westphalia

Michaela Schneider, vice-chair of the ‘Values Union Association’ (Werteunion) in North Rhine-Westphalia

Silke Schröder, chair of the ‘German Language Association’ (Verein Deutsche Sprache)

Ulrich Vosgerau, former member of the board of trustees for the Desiderius Erasmus FoundationTHE REST

Alexander von Bismarck

Henning Pless, far-right, esoteric practitioner of alternative medicine

An IT businessman and die-hard Nazi

An Austrian neurosurgeon

Two Hotel employees

Act 1, Scene 1: A lakeside hotel

The large 1920s hotel lies on the outskirts of Potsdam. It has a tiled roof and view onto the nearby lake Lehnitz. The first guests arrive on Friday evening. A white 4×4 from Lower Saxony rolls up, a song by the band Frei.Wild blaring out of the window: Wir, wir, wir, wir schaffen Deutschland (We, we, we, we’re creating Germany).

More guests arrive the next morning. Inside the hotel, they head across the parquet floor towards a white table set with around thirty plates, each with a folded napkin. Many of them have received personal invitations containing all the relevant information about the event. The invitations, from the “Düsseldorf Forum”, as the group is calling itself, talk of an “exclusive network” and a “minimum donation” of €5,000. Raising funds is a “core task of our group”, they state. And they are actively pursuing this goal, it seems, by soliciting money from wealthy businesspeople who want to support far-right alliances in secret. “We need patriots who are ready to act and individuals who will support their activities financially”, it says in the invitation. Once at the meeting, the event organisers would announce a “neutral bank account”, or the donation could also be paid in cash, readers were assured.

But what are the donations for?

The purpose of the donations is hinted at in the invitations, which are signed by the organisers Mörig, the dentist, and Limmer, the former Backwerk shareholder. In another copy of the invitation seen by CORRECTIV, Mörig talks of “an overall concept in the sense of a masterplan”. The masterplan will be presented, he proudly announces, by “none other” than Martin Sellner, the long-standing leader of the far-right Identitarian movement. Anyone who attended this weekend in the hotel knew what it would be about.

Act 1, Scene 2: A masterplan to rid the country of immigrants

Sellner, author and a leading figure in the European New Right, is the first speaker of the day. In Mörig’s introduction, the audience are told that Sellner has “the masterplan”, which centres around one key idea: “re-migration”.

It’s Sellner’s idea of re-migration that should be the focus point of this gathering, Mörig says. Everything else – covid restrictions and vaccinations, the issues of Ukraine and Israel – are all bones of contention on the right. Their stance on re-migration, however, is what unites them. Mörig thinks it will be decisive in the question of “whether or not we in the West will survive.”

The majority of presentations and discussions held today will focus on this concept.

Now Sellner takes the floor. In his speech he details what re-migration would mean in Germany. There are three target groups of migrants, he explains, who should be extradited from the country – or, as he puts it, “foreigners” who should undergo “reversed settlement”. They are: asylum seekers, non-Germans with residency rights, and “non-assimilated” German citizens. It is the latter that, in his view, would pose the biggest “challenge”. In other words, Sellner’s plan would divide German residents into those who would be able to live peacefully in Germany and those for whom this basic human right would no longer apply.

The scenarios sketched out in this hotel room in Potsdam all essentially boil down to one thing: people in Germany should be forcibly extradited if they have the wrong skin colour, the wrong parents, or aren’t sufficiently “assimilated” into German culture according to the standards of people like Sellner. Even if they have German citizenship.

It’s a scenario that would contravene the citizenship rights and principle of equality between citizens which are a bedrock of the German constitution.

The far-right concept of ‘re-migration’

Sellner’s ideas are nothing new. In his book “Regime Change from the Right”, released in 2023 by the German far-right activist Götz Kubitschek’s publishing house, he outlines how:

“The main goal of the Right” is the preservation of “ethnocultural identity and integrity”, which requires “a radical turnaround” in order to stop the current “population exchange”. To achieve this, “a policy of re-migration” is necessary. Sellner calls for a “revision” of existing citizenships and refers to “relevant concepts of right-wing parties and movements” in this area. The book isn’t hard to understand. It’s about preparing for mass deportations.

The close ties between Sellner and certain AfD politicians that are evident in this meeting are nothing new. Kubitschek’s publishing house offers Sellner’s book as a set along with Maximillian Krah’s manifesto – Krah is the AfD’s frontrunner for the European elections. His book, “Politics from the Right – a Manifesto”, calls for the abandonment of universal human rights, and also advocates the “re-migration” of “citizens”. Krah argues that “even if a restrictive immigration policy could be politically enforced in 10 years’ time, the question remains as to what would happen to all the immigrants already in the country.” He estimates that by then these immigrants would number around “25 million […] 15 million of which will be German citizens”. He fears that “even in ten years’ time, there will be no political majority willing to expel these people from the country against their will, let alone a way to do so legally under constitutional and international law”.

Act 1, Scene 3: No objections from the AfD, despite recent public discussion to ban the party on grounds of extremism

Many supportive questions follow this speech. There are no objections to the “masterplan” in principle, only concerns about its feasibility.

Silke Schröder, a property developer and board member of the right-leaning Verein Deutsche Sprache (German Language Association), wonders how re-migration would work in practice. Surely if a person has the “appropriate” passport it would be ” impossible”, wouldn’t it?

For Sellner, this is just a detail. A “high level of pressure” will be exerted on people to adapt, he says, via “customised laws”. Re-migration won’t happen overnight; it is “a project that will take decades”.

There is certainly no opposition to the idea from the AfD members in the room. On the contrary, MP Gerrit Huy emphasised that she had been pursuing this goal for years.

Huy claimed that she had presented the party with a “re-migration concept” when she first joined seven years ago. Plans for re-migration were the reason the party no longer opposed the government’s plan to lift the ban on dual citizenship, she said, “because then you can take away the German one, and they still have one left”. Huy’s statements suggest that immigrants with a German passport have the potential to be lured into a trap.

The AfD parliamentary group leader for Saxony-Anhalt, Ulrich Siegmund, is also in the room. It is he who will, later on in the day’s proceedings, appeal for donations. He has considerable influence within the AfD; the party is currently polling in first place in Saxony-Anhalt. His sales pitch, very much in keeping with the “masterplan” of Sellner, details his ideas to change the image of German streets. Foreign restaurants would be put under pressure. Living in Saxony-Anhalt should be made “as unattractive as possible for this clientele.” And that could be accomplished very, very easily, he claims. His comments could have consequences for the region’s upcoming elections.

Buoyed by their recent surge in popularity, the AfD is feeling optimistic. The general shift to the right in the country has given the party a boost. It is currently ahead in the polls on over 30% in several states including Saxony and Thuringia – well ahead of the CDU, SPD and the Greens. However, the party is also under pressure. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution(Bundesverfassungsschutz), Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, has classified the AfD’s branches in Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt and Saxony as right-wing extremist groups. More recently, it classified the North Rhine-Westphalian AfD youth wing Junge Alternative as a suspected extremist group. The reasons given were its proximity to the Identitarian movement, its “ethno-nationalist” views, and its “contempt for people with an immigrant background”.

The debate about whether the AfD should be banned is gaining increasing momentum. A petition calling for a party ban has gained over 400,000 signatures, and CDU MP Marco Wanderwitz is currently gathering support in the Bundestag (German parliament) to call for a motion to ban the party.

The AfD itself, however, still insists that it is a democratic force. “The AfD is a political party under the rule of law, and thus pledges its unequivocal allegiance to the German nation which includes all those with German citizenship,” it claims on its website. Immigrants with German citizenship are “just as German as the descendants of a family that has lived in Germany for centuries”. “For us, there are no first and second-class citizens,” they go on.

The statements by AfD politicians at the Potsdam meeting suggest very different beliefs. Here, protected from the public eye, they have no problem proclaiming their racist ideals. In fact, there were no significant differences between their views and those of the far-right ideologues.

Act 1, Scene 4: A Nazi Utopia

Outside, the snow is turning to slush. But inside the hotel spirits are high. Gernot Mörig is telling guests how he is normally a rather pessimistic type, but today he is feeling hopeful. And that’s thanks in part to Sellner’s “masterplan”.

The masterplan even includes a destination to “move people to”, a so-called “model state” in North Africa, that would apparently provide space for up to two million people. There would even be educational and sport offers there. And anyone who lobbies on behalf of refugees could join them there, Sellner added.

Sellner’s concept is eerily reminiscent of the Nazi’s 1940 plan to deport four million Jews to the island of Madagascar. It is unclear whether Sellner had this historical parallel in mind when devising his plan. It may also be mere coincidence that the organisers of the event chose a location less than 8 kilometres away from the villa where the Wannsee Conference took place – the meeting where the Nazis coordinated the systematic extermination of the Jews.

Back in the hotel, Sellner turns to another inflammatory topic for the far-right, the problem of the so-called “ethnic vote”. He’s even registered the term as a domain name. According to Sellner, the problem is “not just that foreigners live here. They also vote here.” “Ethnic voting” means that immigrants are likely to vote for “immigration-friendly” parties.

Sellner’s arguments are not only attempts to delegitimise elections, they also treat German nationals as foreigners in their own country. According to the German office for national statistics (Statistisches Bundesamt), 20.2 million Germans have a ” history of immigration “, meaning that they or their parents immigrated to Germany since 1950.

The events in the Potsdam hotel make clear how the strategies of various far-right actors and organisations intertwine. Sellner provides the ideas, the AfD politicians take them on and bring them to the party. Others in the background take care of the networking and bringing in wealthy sympathisers and supporters from the conservative middle-classes. And the debates always revolve around one question: How can a homogonous ethnic community be achieved in Germany?

Act 2, Scene 1: Influencers to help roll out the masterplan

Discussion now turns to the practical details, the steps that need to be taken. Mörig wants to select a committee of experts to fine tune the details of this plan for mass deportations. These experts will ensure the masterplan is executed “ethically, legally, and efficiently”, so that the racially motivated forced displacement of people has the guise of a legal migration policy. Mörig already has a candidate for the committee in mind: Hans-Georg Maaßen, the former head of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesverfassungsschutz), Germany’s domestic intelligence agency.

Maaßen’s name comes up a number of times over the over course of the weekend. According to several reports, he’s due to announce the launch of his own political association in January. The attendees of the Potsdam meeting already know all about it. Although they mention the new group on several occasions, they don’t seem to take it too seriously. They are more concerned with their own plans, and how they will be realised when, in Mörig’s words, “a patriotic force has come to power in this country.”

The group’s focus now turns to how the idea of re-migration can be turned into a political strategy. Sellner says that “metapolitical and pre-political power” must be built up in order to “change public opinion”. An active political frontline must be ready to support the incoming right-wing government in Germany after the election.

And part of this support, as is made clear during the presentations and speeches, has to be financial. There is talk of influencers, propaganda, campaigns, and university projects. The tools to establish a right-wing anti-establishment climate. And ultimately the tools to weaken Germany’s democracy by questioning elections, discrediting the constitutional court, suppressing opposing views and censoring public service broadcasting.

Act 2, Scene 2: As if the balance of power had already tipped

One speaker follows the next, the talks last around an hour each. Halfway through lunch is served, the waitress seems irritated by the large number of guests she has to accommodate.

In the afternoon, it’s Ulrich Vosgerau’s turn to speak. He is a lawyer and was a member of the board of trustees of the AfD-affiliated Desiderius Erasmus Foundation, and is currently representing the AfD in the German Constitutional Court in a dispute over the foundation’s funding.

He talks about postal votes, legal processes, the secrecy of the ballot, and his concerns about voters of Turkish origin who, he claims, are unable to form an independent opinion. Vosgerau suggests drafting a letter which would cast doubt on the legitimacy of the upcoming elections. The more people took part, the higher the probability of the letter’s success. His speech is met with applause.

Vosgerau and others speak as if the balance of power has already tipped in their favour. They clearly believe they are on the verge of a breakthrough. Mario Müller, a member of the Identitarian movement and violent offender with a number of convictions to his name, is currently serving as a research assistant to the AfD MP Jan Wenzel Schmidt. In his speech, Müller also talks as if victory were already in sight.

Act 3, Scene 1: The Mörig Clan

The hotel’s lattice windows offer glimpses of the attendees of this secret meeting. The large dining hall exudes an atmosphere of old-fashioned splendour, a harpsicord in one corner, a grandfather clock in another. Many of the guests are in suit and tie.

Things seem to be going well and plans have been worked out, or at least outlined. But everything hangs on funding, a fact Gernot Mörig is well aware of. In the 1970s, Mörig was head of the ‘League of Patriotic Youth’ (Bund Heimattreuer Jugend), a far-right youth organisation promoting Nazi ‘blood-and-soil’ ideology. A splinter group, the ‘Young German Patriots’ (Heimattreue deutsche Jugend) was banned in 2009 because of its neo-Nazi agenda. The group was so right-wing, in fact, that Andreas Kalbitz, former leader of the AfD in Brandenburg, was expelled from the party when it was discovered that he had been a guest at one of their camps.

It was Mörig who selected the guests and set the agenda for this secret meeting. It was he who wrote about the “masterplan” in his invitations and asked for donations from those invited. During the event he asks guests to “discreetly” hand over their cash donations to his wife. Later, he explains that the money he collects will be used to support smaller organisations, like Martin Sellner’s.

This means that every guest who donated money did so in the full knowledge that they were funding the Identitarian movement and Sellner himself. But Mörig is about to ask for even more.

He presents the attendees with a list of supporters who allegedly want to donate money or have already done so, including individuals not present at the event. Christian Goldschagg, founder of the gym chain Fit-Plus and former shareholder in the Süddeutscher publishing house; Klaus Nordmann, a middle-class businessman from North Rhine-Westphalia and major AfD donor; Alexander von Bismarck, for example, who attracted attention with his understanding of Russia and a bizarre campaign last year, is also sitting in the room. Mörig is forthcoming with names. He brags about those who have already donated “high four-figure sums” and those who have promised to do so. Previously, the donations were channelled through his banker brother-in-law’s private account, but he now has plans for a more professional solution. Those who feel more comfortable doing so can leave a cash donation with his wife, but “by the next meeting we will probably also have an unregistered association” through which bank transfers can be made, he tells the guests.

Act 3, Scene 2: AfD politician solicits millions in direct donations

Ulrich Siegmund, the AfD parliamentary group leader for Saxony-Anhalt, is also in need of money. He is already thinking about the upcoming elections and the campaign adverts he wants to send out, preferably directly into peoples’ letterboxes. He wants every voter to be written to at least once. Traditional radio and television advertising will also be necessary. And he needs money “additional to what is provided by the party” – an additional €1.37m to be precise. This could be an attempt to bypass the official party funds by channelling money directly to him. The AfD already has several donation scandals to its name.

Official party donations are “of course by far the safest way” to donate, says Siegmund. “Nevertheless,” there are other “absolutely legal ways to make donations.” He suggests going through “agencies” and “third parties”. Guests are invited to come and discuss the options with him separately in order to find “the best option for each individual.”

Act 3, Scene 3: Alice Weidel’s right-hand man

The fact that parts of the AfD have close ties with neo-Nazis and the New Right is nothing new. Until now, however, the party has blamed the problem on regional and local branches.

But a senior AfD politician was in attendance at this meeting with right-wing extremists in Potsdam. His name is Roland Hartwig, a former AfD MP now serving as personal aide to the party’s leader, Alice Weidel. According to several AfD government insiders, Hartwig is the “unofficial general secretary of the party,” someone who holds significant sway on the party’s highest levels of decision-making.

Hartwig professes to being a big fan of Sellner’s new book, which he is “greatly enjoying”. He also talks of the “masterplan” and then goes on to say that the AfD is currently drafting a prototype of a lawsuit against German public broadcasters. This is in addition to a campaign he says they are planning which will show how overfunded the broadcasters are.

Mörig’s son also has a plan to present at the conference. It fits in nicely with Sellner’s ideas. Arne Friedrich Mörig wants to set up an agency for right-wing influencers. Hartwig mentions the possibility that the AfD could co-finance the agency. This would enable them to influence elections, Hartwig points out, especially via young people. “The generation that has to change the political game is already there”, the says, and the AfD plans to target young people on platforms such as TikTok and YouTube with content that will normalise the party’s ideas.

According to Hartwig, the next step in this project will now be to present the plan to the AfD’s national party board, and to convince the party that it will benefit from an investment in Mörig’s influencer agency.

Towards the end, Hartwig makes a pivotal statement: “The new Party Board, which has now been in office for a year and a half, is open to this issue. We are therefore prepared to take money in hand and pursue issues that do not directly benefit the party alone.”

Hartwig gives the distinct impression that he is acting as an intermediary for the AfD’s party board, tasked with communicating the content of this meeting to them. He had not responded to our questions about the meeting at the time of going to press.

Epilogue

The following evening everything is quiet. The hotel seems almost completely deserted. Only the flickering of a TV screen can be seen through the window of one of the suites.

What have we learnt from this meeting?

That there is a retired dentist who has a conspiratorial network of fellow far-right extremists. That representatives of the AfD were willing to meet with radical right-wing activists and neo-Nazis. That they have a ‘masterplan’ to deport German citizens because of their ‘ethnicity’ – a plan which would undermine Articles 3, 6 and 21 of the German constitution. And that there are a number of wealthy potential donors for this project. We’ve learnt that there is an expert in German constitutional law who has sketched out legal methods to systematically cast doubt on democratic elections. That there’s an AfD politician who wants to organise election donations that would bypass the party. And that there is a hotel owner in Potsdam who earned some money to cover his costs.