We have translated this article by Capulcu on all the costs of chip production, AI and the advancement of technology itself. This text deliberately focuses on the material side of AI in the context of multiple intertwined crises, especially the ecological crisis linked to the crisis of new wars for a multipolar world order.

CHIP PRODUCTION IN THE MULTI-CRISIS

The material side of artificial intelligence

Introduction

In most debates, the hype surrounding so-called “artificial intelligence” (AI) appears to us in a purely virtual form; as the promise of a virtually unconditional automation of almost all areas of life through a profound reorganisation of human-machine interactions based on human language. We have already discussed the political and economic consequences of this technological leap, particularly the increase in social inequality and dependence on a technocratic oligopoly (= the few guardians of the major language models) in “The Gold Diggers of Artificial Intelligence“.

In “ChatGPT as egemony booster“, we analysed a politically relevant narrowing of broad discourses through an exaggeration of the mainstream paired with an expected shift to the right as a hegemony amplifier. The interaction of social media with language generators such as ChatGPT demonstrably reduces discursive diversity and promotes social fragmentation.

This text will deliberately focus on the material side of artificial intelligence in the context of multiple intertwined crises – particularly the ecological crisis in connection with the crisis of new wars for a multipolar world order. Our first text Climate – the Green Vehicle of the AI offensive has already touched on this topic. Regarding climate destruction, AI is turning out to be a fire accelerator and not, as is often fantasised, a central solution tool for an optimisation problem that is too complex for humans.

The massive expansion of AI data centres consumes an enormous amount of energy, and not just for training and operating the large language models (a single training run of the current language model GPT-4 costs 64 million dollars in electricity). The development and production of the chips consume vast amounts of energy and water – in addition, rare metals such as germanium and gallium are required the extraction of which causes massive environmental damage. Most computer hardware has therefore already had most of its climate-damaging effect before it is switched on for the first time (1). In addition to the energy-intensive operation of the data centres (added power consumption of the processors + their active cooling), the disposal of the high-performance hardware, which is sometimes used for just two years, also contributes to the enormous ecological footprint.

The USA and the EU are currently spending a lot of money and other resources to rebuild a “domestic” semiconductor industry – to secure their crisis-ridden technological dominance over their declared “system rival” China. Artificial intelligence in particular has been identified as a key technology: a technology that would be inconceivable without the most modern microchips – designed by Nvidia in Silicon Valley, USA and manufactured by TSMC in Taiwan with globally unique exposure machines from ASML in Eindhoven, Netherlands. Meanwhile, China has experienced an unprecedentedly rapid economic and technological rise – with no end in sight, even if Chinese economic growth has slowed somewhat in recent years. In some core areas such as electromobility, high-speed trains, renewable energies and 5G, Chinese companies are now leaving their Western competitors behind. If neither side can assert its interests by other means, the currently escalating trade war threatens to turn into a hot war. This raises the practical question of whether and how war and the further militarisation of society can be stopped.

Chips have been an important military technology since their inception. We also interpret the planned chip factories as part of the necessary economic disentanglement in preparation for war. These chip factories that are now also being built here in Germany (e.g. Intel in Magdeburg and TSMC and Infineon in Dresden) are therefore points where resistance can and should begin to formulate a left-wing critique of both progressive ecological destruction and the normalisation of the logic of war in the current multiple crisis. The chip industry is both highly specialised and globally integrated: entire supply chains therefore depend on the products and knowledge of individual companies and locations.

This text is an invitation to debate for those who are critical of domination, ecological and anti-militarist. We want a discussion and practice that opposes further militarisation and environmental destruction. Let’s break out of this future now – Keep the future unwritten!

Chip boom with environmental consequences

Chip maker Nvidia is currently one of the biggest beneficiaries of the AI boom. Production of high-end graphics chips has long been unable to keep up with demand. Since the publication of ChatGPT at the end of 2022, the value of the company has increased around sixfold to over two trillion dollars – even though Nvidia does not produce chips itself, but merely designs and commissions them. Nvidia develops special high-performance chips for the machine learning of so-called artificial neural networks, which are particularly effective at performing simple arithmetic operations in parallel with many interconnected “processor cores”.

According to an empirical prediction made in the 1960s (and still valid today), Moore’s Law, the number of circuits on the same surface doubles every two years at the latest as a result of advances in lithographic processes in chip production. This is roughly equivalent to a doubling of chip performance. This leads to a quasi-cyclical replacement of computer hardware with newer, more powerful hardware in many application areas.

This constant replacement causes massive environmental damage. This (cyclical replacement) production effort for computer chips is increasing massively, especially in a world of ever-increasing data processing and networking, as envisaged by the technocrats, in which everything is supposed to communicate with everything else (smartification via 5G networks / Industry 4.0).

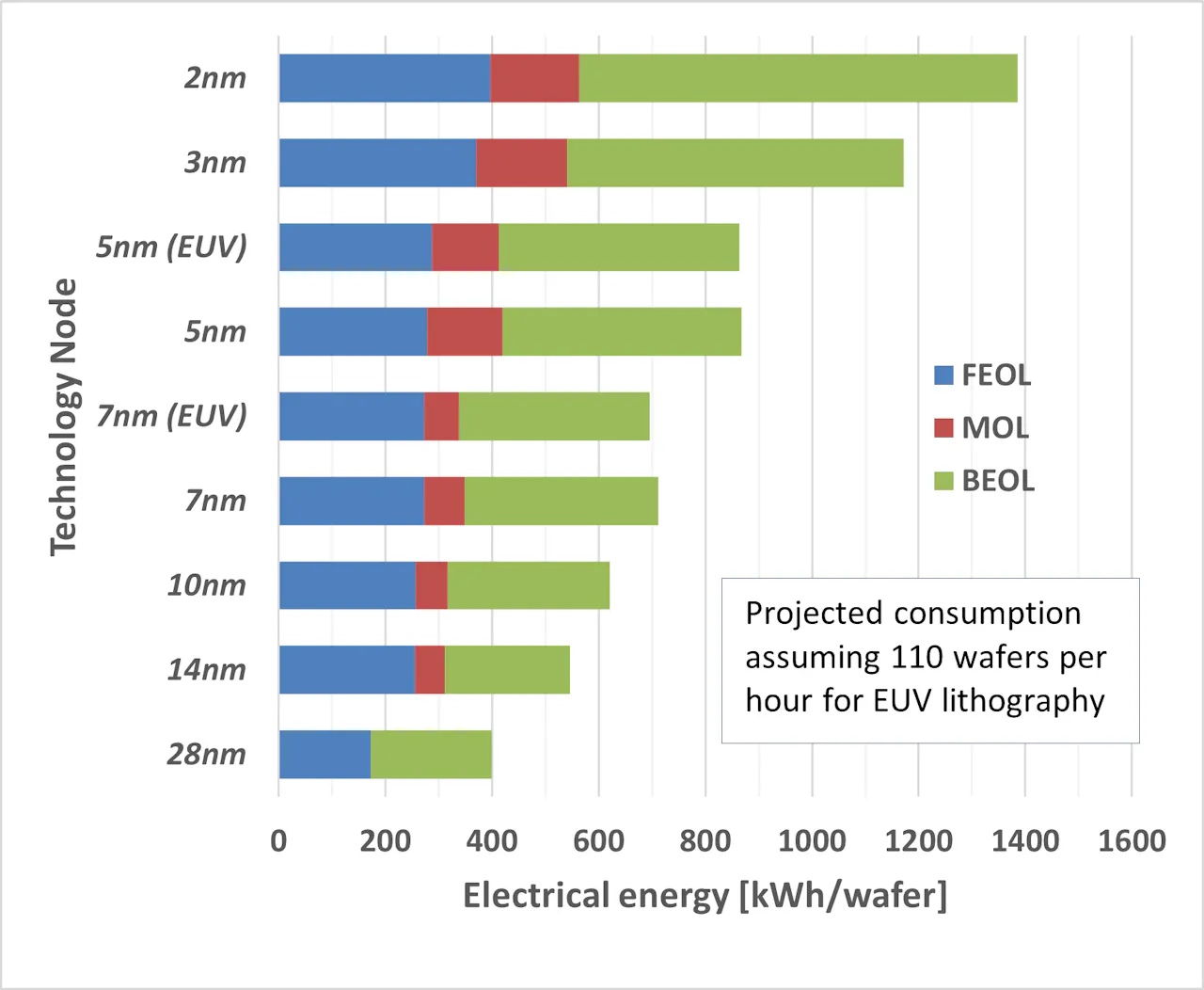

In addition, the environmental impact of producing a single chip increases with increasing power density: it takes three to four months for a silicon wafer (a wafer is a thin slice of semiconductor, such as a crystalline silicon, used for the fabrication of integrated circuits and, in photovoltaics, to manufacture solar cells” TN) to pass through the various processing stages to become a finished product. The wafers are elaborately processed in an ever-increasing number of steps in which microscopic layers are deposited, patterns are burned in and unnecessary parts are scraped off in fully automated processes.Rinsing with large volumes of ultrapure water is an important part of this process.

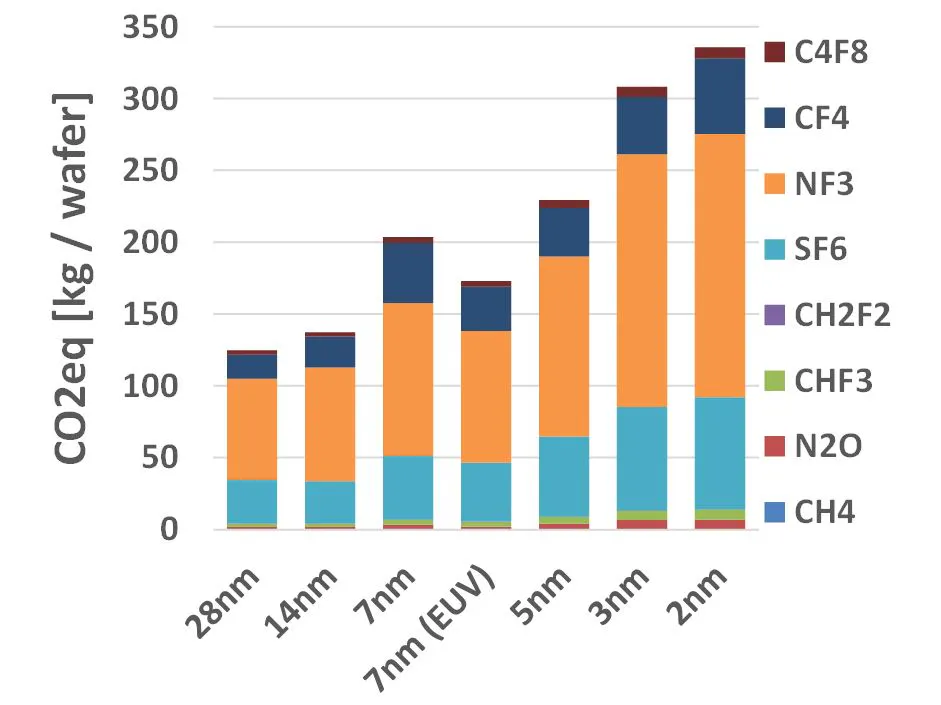

Assuming a silicon wafer of the same size as a computer chip, the latest 2nm process technology requires significantly more electricity (x3.5) and ultrapure water (x2.3) for production than the older 28nm technology. Greenhouse gas emissions (in CO2 equivalents) increase by a factor of 2.5 (per computer chip). (2)

For Taiwanese chipmaker TSMC, the world’s largest contract manufacturer, which also supplies Apple, among others, this means that TSMC is currently responsible for six per cent of Taiwan’s electricity consumption. The environmental impact is disastrous, as almost half of Taiwan’s electricity comes from dirty coal power. The company uses 150 million litres of water a day to clean wafers with ultra-pure water. This is despite the fact that Taiwan has been suffering from a drinking water shortage for years. A lack of rainfall and periods of drought have caused water levels in reservoirs to drop significantly. Some cities in Taiwan have already had to ration drinking water and reduce water pressure to avoid disrupting global supply chains for key semiconductors. The government is having wells drilled across the country and is trying to appease angry rice farmers with compensation payments. (3)

In a paper published in October 2020, researchers at Harvard University (4) used publicly available sustainability reports from companies such as TSMC, Intel and Apple to show how the proliferation of computers is increasing their environmental damage. Information and computing technology is expected to account for up to 20% of global energy demand by 2030, with hardware responsible for a larger share of this environmental footprint than the operation of a system, the researchers say: “Most of the carbon footprint comes from chip manufacturing, not from hardware use and energy consumption.”

As a result, the most advanced chipmakers already have a larger carbon footprint than some traditionally polluting industries, such as automobiles. For example, company data shows that in 2019, Intel’s factories will already consume more than three times as much water and generate more than twice as much waste classified as hazardous as General Motors’ plants.

Semiconductors are the material side of the information technology attack

The concept of technological attack helps us to develop a critique of technology as a critique of power and society. To understand why we characterise innovation and technological ‘progress’ as an attack,

“We must realise that it is precisely the capitalist theorists and strategists of innovation who understand innovation as a comprehensive offensive, as a comprehensive shock. A shock aimed at the destruction and reorganisation not only of work, but of society as a whole in all its spheres, from work to transport, family, education and culture. They do not see innovations simply as ‘inventions’. They see them as the use of basic technologies that have the potential for widespread destruction or “disruption” and reorganising subjugation and reorganisation. ” (5)

The information technology attack we are talking about is not the first attack on innovation:

“In the so-called “industrial revolution”, new machines (steam engines, automatic looms, etc.) were used not only to destroy traditional forms of work and the habits of life based on them, but also to ‘shake up’ the entire population. […] [A] subsequent wave of violence was launched around the electrical and chemical industries. It was closely linked to the forms of behavioural discipline and mental conditioning of Taylorism and Fordism. Its material core lay in the attack of the technology of the electric assembly line and its utopia on society as a whole. As its central ‘inventor’ or ‘innovator’, the American Frederick Taylor himself explicitly described his system as a ‘war’ against the autonomy of workers (mostly migrant farm labourers) and their unregulated way of life. ” (6)

Information technology as a technique of domination

Today, information technologies are a central pillar in the stabilisation and enforcement of capitalist rule worldwide – both civilian and military/police. Ubiquitous computing (for the ubiquitous collection and availability of all everyday data, e.g. via smartphones) and artificially intelligent modelling of this data (e.g. for predicting behaviour), especially with machine learning techniques, have only been made possible by the enormous increases in storage and computing capacity of microchips over the last two decades.

Economic productivity has long depended on the quality and availability of IT applications and their hardware, especially where labour is expensive. The automotive industry in Germany felt the effects of this during the coronavirus pandemic, when production was temporarily halted because the necessary chips or simple microelectronics were not available from the Far East.

The repertoire of government techniques that ultimately rely on information technologies and the computing power they require, also known as ‘digitalisation’, is quite diverse. Nudging, for example, seems to fit in well with the EU’s (post-)democratic self-image. After all, this technology makes it highly likely that the desired behaviour will occur. Another example is the Chinese government’s social credit system, which exerts strong pressure on individuals to behave in a socially compliant manner. These different and complementary techniques of domination lead to a profound transformation of societies. They are therefore an attack on people’s lives and work. The governments of both – supposedly completely different political systems – recognise the opportunities offered by the development of digital technologies and promote their implementation. A central effect of the technological assault is the creative destruction (Schumpeter) of existing social structures and forms of sociality. This serves two important purposes. On the one hand, new areas of human life are constantly valorised by the attack in the sense of original accumulation for capital. Secondly, the technological attack makes it possible to (roughly) predict and control social behaviour. In other words, the aim is to create a predictive control society.

Computer chips are a vital resource for the war industry

Soon after coming to power in 1933, the Nazis began to prepare the German economy for war. The proportion of GDP spent on armaments rose from 1% to 20% between 1933 and 1938. Among the measures taken was the construction of steelworks, which were highly uneconomical because they could not compete with cheap (e.g. Soviet) steel on the world market. The Nazi state massively subsidised the industry, citing the need for economic “self-sufficiency”. Today, those who want to make their national economies “independent” of foreign goods and thus ready for war no longer subsidise steel, aluminium or rubber factories, but above all chip factories and energy companies. The massive increase in arms spending in many countries since the start of the war in Ukraine, coupled with the pursuit of economic “independence” in key industries such as semiconductor production and energy supply, as well as the simultaneous ideological arming (“ruin Russia”), serve a common goal: “becoming ready for war”. At least that’s what the German war minister called it. Once this preliminary goal has been achieved, it is only a small step to actually waging war. Russia has recently shown how quickly this can happen.

Computer chips have been an important military technology since their inception. The starting point for the development of the first computers was the Second World War. The first decades were heavily influenced by military investment and requirements. Although the proliferation of PCs, laptops and eventually mobile devices in the civilian sector since the 1970s has led to an increasingly digital society, military applications continue to be a major driver of semiconductor development. Huge research and development projects have been driving military computing technologies for decades.

Even conventional weapons such as missiles, bombs, etc. have long been equipped with chips. During the war in Ukraine, Russia allegedly had to develop microchips in order to circumvent export bans on white goods (washing machines, etc.) and install them in its own weapon systems.7 As weapon systems become increasingly networked and autonomous, the performance of IT systems, and thus the availability of microchips that provide the necessary computing power, will play an increasingly important role in determining military strength. More and more AI applications are finding their way into military IT systems: chatbots à la Chat-GPT are being implemented in battle management systems (e.g. “AIP for Defence” by Palantir Inc.8 ) and in simulation systems for the development of complex decision-making processes, e.g. for the defence against enemy drone attacks (e.g. “Ghostplay” by the Bundeswehr Centre for Digitalisation and Technology Research9 ) or for propaganda purposes and targeted disinformation campaigns with the help of AI-generated fake images and texts. The main language models have become dual-use (civilian+military) even before the company OpenAI removed the civilian clause for the use of ChatGPT in January 2024.

Cutting-edge semiconductors at the heart of US-China battle for technological supremacy

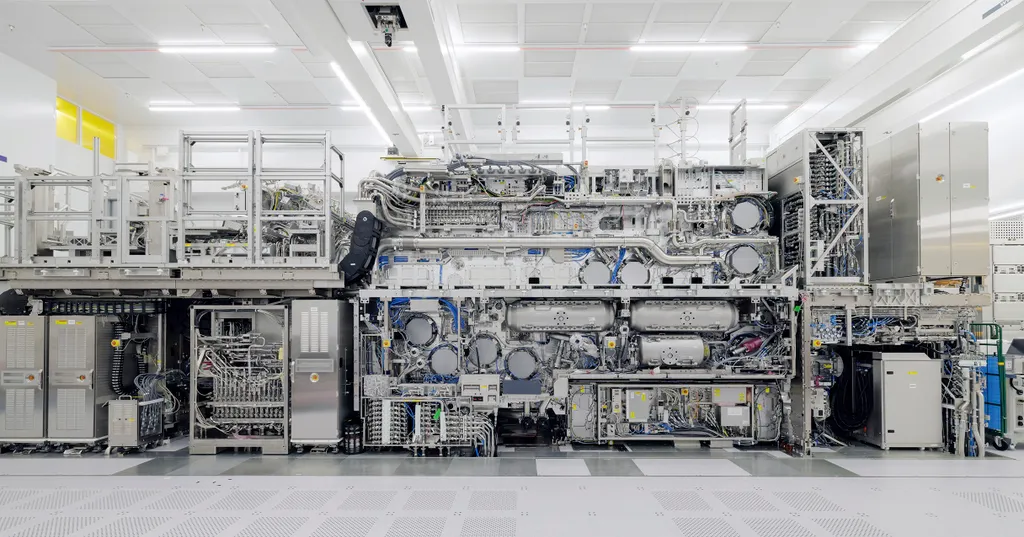

In March 2023, under pressure from the US government, the Dutch government announced new restrictions on the export of lithography equipment, the exposure machines that are central to the production of ever more powerful chips. Since then, the export restrictions have continued to tighten. The machines made by ASML, the largest manufacturer of chip production equipment with a market share of almost 90%, can now only be exported to China with a special licence. The aim of this measure is to make it more difficult for China to develop its own (high-performance) chip production. China is already the world’s largest producer of chips using obsolete production technologies from 80nm onwards and therefore has a very relevant industry of its own in this sector. However, it is unable to produce the crucial high-performance chips needed for modern servers, laptops, smartphones and graphics cards. The Taiwanese company TSMC has a market share of over 90%, particularly for semiconductors in production technologies below 14nm, although Chinese companies have repeatedly reported decisive breakthroughs in recent months.10 TSMC also produces well over half of all chips worldwide. The outsourcing of semiconductor production from the capitalist centres to Taiwan across the Pacific was part of neoliberal globalisation and the associated deindustrialisation in many of the centres themselves.

Overall, the semiconductor industry is highly specialised and (global) supply chains depend on individual companies or factories in many locations. The aforementioned Dutch company ASML is the only company in the world capable of building and maintaining state-of-the-art production facilities. ASML itself depends on products from highly specialised suppliers. The high-performance lasers used to expose the wafers were developed by Trumpf, a mechanical engineering company based in Ditzingen, Germany. The mirror system used to guide these lasers into the target was developed by Zeiss of Oberkochen. Zeiss also boasts that 80% of the world’s microchips are produced using its own optical systems. (11) But that’s not all – hundreds of chemicals are needed in semiconductor production itself. Some of these can only be produced by a few companies. In Germany, these include BASF and Merck. And – you guessed it – Merck also claims that the chemicals it produces are contained in almost every microchip in the world. Because of their importance in semiconductor production, the German government discussed restrictions on exports of German chemicals to China in April 2023. (12)

China, in turn, responded in August 2023 by restricting exports of gallium and germanium to the EU. These raw materials are essential for the production of microchips. China is the world’s largest producer of the minerals gallium and germanium. The EU buys 71% and 45% respectively from China. The EU and its main Western ally, the US, are working hard to develop their own raw materials base.

The economic war does not stop at the losses of national companies

The initiatives and investment programmes of the US, China and now the EU to become less dependent on Taiwan for semiconductor production are not new, but date back at least to the mid-2010s. This is based on the realisation that microchips are not just any industrial product, but a “key technology”, as the current debate over export bans on Nvidia chips for AI training shows. (13) By “becoming more independent”, “de-coupling” or – as the EU calls it – “de-risking”, the governments of these countries mean first and foremost that their ability to make capitalist profits or to wage war should not be restricted by other states. This is by no means a unilateral sanctions or protection policy on the part of the Western states. China is also taking tough measures to gain ground in the “chip war”. For example, the Chinese government has banned large companies in its own country from buying (memory) chips from the US company Micron Technology. These chips can be manufactured in China itself – even though the market in this segment is (still) dominated by others.

All the major software tools for chip design are owned by Western companies. China has less than one per cent of the global chip design market. The exposure systems for high-performance chips can only be produced by the Dutch company ASML. Chinese companies, on the other hand, can only compete in the global market with very outdated production technologies. This means that the US still has a certain lead over China in the chip sector, but it is shrinking fast. The US and the EU are also just as “dependent” on production in Taiwan as China. Given their economic and military importance, the vulnerable supply chains of chips produced in Taiwan represent an enormous risk for governments. None of them can be sure that they will be able to maintain these supply chains through military threats and, if necessary, war. This situation gives rise to the hope that the risk of war is considered too high on all sides. This is because the US government wants to do everything in its power to prevent China from catching up, both in terms of the necessary expertise in chip design, for example, and in terms of existing manufacturing capacity. For its part, the Chinese government’s Made in China 2025 programme aims to make China the world’s leading manufacturing power by 2049. China therefore believes that its own economy can benefit more from the “rules-based world order” than those who have been its main beneficiaries since its inception after the Second World War.

The selective rejection of free trade in the US and the EU confirms that this view is shared there. The neo-liberal dogma of recent decades is increasingly being questioned in these countries, too, against the backdrop of successful Chinese state interventionism. In order to maintain its position of global power, the US government is willing to inflict economic damage even on large technology companies. Apple, for example, is less than enthusiastic about the US’s economic protectionism towards China. After all, the company’s devices are assembled there, even though they are designed in California and the required chips can only be produced in sufficient quality and quantity by TSMC in Taiwan. Unlike companies such as Google, which fear Chinese competition, especially in the field of artificial intelligence, Apple has benefited from the globalised division of labour with China and wants to continue doing so.

China has risen from a “developing country” to a “system rival”

Governments in the EU and the US have recognised China as the first serious “systemic rival” since the collapse of the Soviet Union. They recognise that the People’s Republic has the potential to become the world’s largest economy and is already outperforming leading Western companies in parts of the high-tech sector. Huawei, for example, is the company that will register the most patents worldwide in 2020. Much of the network technology installed worldwide, such as for 5G, comes from this company. In other key areas, such as artificial intelligence, most scientific publications are now also of Chinese origin (although the quality of these publications is debatable).

From a naïve point of view, it may seem paradoxical that Western countries are fighting China as a rival or competitor. After all, within the “rules-based world order”, China has gone from being one of the poorest “developing countries” to the world’s second largest economy in terms of GDP, thanks to skilful economic policies and opening up to the capitalist world market. The fact that China has been able to do this is a special case that was obviously never intended in this form by those who promised “development” through economic and political opening, but only thought of access to raw materials and markets. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) under Deng Xiaoping relied heavily on foreign investment for economic development. But Western capital was not allowed into the country unconditionally. Foreign companies had to form joint ventures with Chinese companies for their investments. In addition, technology transfer to China and local Chinese suppliers were a prerequisite for investment, and only productive investment (e.g. building production facilities) was allowed, not purely financial investment (e.g. buying shares in existing companies). There was also a very restrictive currency and credit policy. This strategy allowed China to create its own competitive enterprises. The fact that the CCP was able to negotiate these terms with capitalist foreign countries was due to the fact that China had both a huge pool of cheap labour and a corresponding market. The size of the country made it so attractive to foreign capital that the governments of the developed countries made compromises that other countries could not match.

The expectation of the US and leading EU countries that the opening of the market would be accompanied by a political opening has been met only in rudimentary ways, such as the creation of a constitutional state as a prerequisite for capital investment. Many of the techniques of power that have been used successfully elsewhere to make people economically dependent (sanctions, debt, company takeovers, etc.) and to influence civil society (for example, by promoting NGO networks, journalists and activists) could hardly be used effectively from the outside in China. This is not by chance, but because the CCP was well aware of the risks of external influence in opening up the country. If we understand economic opening as a change in strategy by the Chinese elites after Mao’s death, it becomes clear that the continuity with socialist China lies in the CCP’s nationalism on the outside and paternalism on the inside. Transforming China into a country of global importance was the declared goal under Mao (even before socialism). In the real world, this goal can be pursued more effectively by capitalist means than by socialist ones. The fact that the development of the People’s Republic into a state on an equal footing (both economically and politically) will not be easily tolerated by the previous top dogs is shown by the ever louder declarations of hostility in the local media. This is despite the fact that such an economic development could be a ‘model’ for many other countries by the standards of European and US governments. Unlike governments in parliamentary democracies, the CCP can not only plan the course of a legislative period, but also pursue long-term strategies such as the New Silk Road.

Portraying China as an authoritarian, unjust state

Another example of the lack of complexity in the local media is Taiwan. The island off the Chinese mainland is important not only for its semiconductor industry, but also for its geographical location as a naval and air base for controlling the Taiwan Strait, one of the busiest trade routes in the world. The Kuomintang retreated to the island after its defeat in the civil war in 1949. They ruled there as a one-party dictatorship until the 1980s and 1990s, and as an ally of the US against Communist China, they received arms supplies (which they had already been receiving before they fled to Taiwan). In the 1970s and 1980s, the US wanted to break China out of the socialist bloc. To achieve this opening and diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic, it signed three treaties recognising the one-China policy and agreeing to withdraw its own troops and stop supplying arms to Taiwan. US administrations have never really honoured the latter. Democratic President “Yes we can” Obama even authorised $14 billion in arms sales to Taiwan. His successors, Trump and Biden, have continued this policy.

Germany also formally supports the one-China policy under Deng Xiaoping’s guiding principle of “one country, two systems”, which refers to Hong Kong and Macau. So when the German Foreign Minister says: “We do not accept that international law is broken and that a larger neighbour invades its smaller neighbour in violation of international law – and that also applies to China, of course”. Then the talk of two neighbours can certainly be seen as a revision of the one-China policy. After all, the one-China principle means that we are not talking about neighbours but about a single country. It is pointless to argue about the one-China principle, because it is not about social issues or people’s self-determination, but about the territorial claims of states and their governments. Nevertheless, the phrase is remarkable. Because it sets the framework for a possible future military escalation of the conflict with the People’s Republic, in order to prepare the legitimacy of any kind of war involvement. During the war in Ukraine, similar justifications for mobilising the population were so successful that even supposed anti-militarists and anarchists went to war in droves.

The invocation of the fundamental opposition between democracy and autocracy, as heard, for example, from the US president, should be understood against the background of the declared rivalry between systems. While parliamentary democracies constantly integrate new authoritarian elements into their own techniques of rule, they simultaneously point the finger at states such as Iran, Russia or China as the authoritarian other. By contrast, they have fewer problems with comparatively ‘undemocratic’ states such as Saudi Arabia or Turkey. For these policymakers, there is no contradiction in denouncing the fact that demonstrating with a blank poster in Russia leads to arrest, while at the same time restricting freedom of assembly through police laws, expanding state surveillance powers and enforcing a cruel EU border regime. This criticism is not intended to level all differences, but a certain scepticism about the good-evil schema drawn by politicians and the media in this country is certainly appropriate.

What are the reasons for the fact that the above-mentioned conditions are sharply criticised in one case and deliberately ignored in the other? The identitarian construction of the struggle of a “democratic West” against an “authoritarian East” bears considerable structural similarities to well-known nationalist discourses on mobilising one’s own population for war and does not do justice to the complexity of the real power relations. Nationalist discourses have not disappeared, but within the camp of progressive capital (keywords: “turning point”, “the great reset”, “green new deal” and “Bidenomics”) are being supplemented and overlaid by modernised discourses. Even within the “democratic West”, both discourses are not absolute, but remain contested, as Trump, AfD and Christian Lindner show. These discourses are not new. On the contrary, they were a crucial basis of legitimacy for the first bourgeois revolutions.

Conclusion

There are good reasons to oppose the construction of new chip factories. After all, the semiconductors produced there are the material basis of a technological assault that is capitalistically valorising more and more areas of our lives and aiming at a patriarchal society of optimisation and control. Emotions are captured and directed in order to optimise our lives in favour of the interests of its technocratic drivers. This leaves us alone and isolated. Our desire for social community cannot be fulfilled by digital interaction on the screen in ‘social networks’, it can only be suppressed. Divide and rule is not a new technique of domination, but it has taken on a new quality in the social atomisation of digitalised society. Care, community, empathy and physicality are becoming less important. Patriarchy, embodied by the German Minister of War and the ‘feminist’ Foreign Minister, wants to restore the ‘technologically and economically self-sufficient’ state of ‘war capability’.

In order to prevent this, it is necessary to send out unmistakable signals that we are not part of a ‘closed home front’ and that the policy of confrontation with China in the battle for technological supremacy in the field of semiconductor and information technologies cannot be implemented without resistance. The history of social movements shows that it is precisely on the material side that there are many possibilities for resisting (new) technologies as techniques of domination.

New semiconductor factories and the AI hype that accompanies them do nothing to solve the climate crisis. On the contrary, they consume huge amounts of resources. In fact, it makes no sense to manufacture semiconductors in Europe if the factories that assemble our smartphones, for example, are still in East Asia because of labour costs. The climate crisis will not be solved by AI or other technological developments, but will require far-reaching social changes. These changes – we could call them social revolutions – will be prevented rather than promoted by a mental mobilisation for the next wars for technological supremacy.

We would like to see contradictions, additions, agreements, further thinking and political practice!

(1) This also applies to standard components such as laptops and smartphones.

(2) The environmental footprint of logic CMOS technologies, IMEC Studie, M.Bardon, B. Parvais (2020)

https://www.imec-int.com/en/articles/environmental-footprint-logic-cmos-technologies

(3) https://taz.de/Oekologischer-Fussabdruck-von-KI/!5946576/

(4) U. Gupta et. al. (2020), Chasing Carbon: The Elusive Environmental Footprint of Computing, http://arxiv.org/pdf/2011.02839

(5) IT – The technological attack of the 21st century” in DISRUPT,

https://capulcu.blackblogs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2018/10/Disrupt2018-11web.pdf

(6) Ebda.

(8) „AIP for Defense“, Palantir, https://www.palantir.com/platforms/aip/defense/ .

(9) „Ghostplay“, dtec.bw, https://www.ghostplay.ai/ .

(10) https://www.ecns.cn/news/sci-tech/2023-11-29/detail-ihcvixpi0428703.shtml und https://www.reuters.com/technology/huaweis-new-chip-breakthrough-likely-trigger-closer-us-scrutiny-analysts-2023-09-05/

(13) https://www.reuters.com/technology/how-us-will-cut-off-china-more-ai-chips-2023-10-17/

(14) https://www.akweb.de/bewegung/daniel-fuchs-es-braucht-eine-linke-china-perspektive/